Focustro: Development Notes for a Replicating React Application

Contents:

“Offline-first”

There is a an approach to application development sometimes called ‘offline first’ whereby the application stores its data locally (for example, in IndexedDB) and can replicate its data to a remote server.

I’m looking for a better name for this because, for me at least, the main benefit of these applications is not that you can use them without an internet connection:

- The application is more responsive, because it can work without waiting for network requests.

- A replication strategy that doesn’t lose data means that the user can have multiple tabs or devices with the application open, and lets multiple users collaborate on the same data.

- You do not need a complicated backend. Once the replication protocol has been implemented, that’s mostly it!

- You can immediately use the application without creating an account.

There are a number of libraries which help you build these applications (e.g. RxDB, Dexie) but I wanted to explore building up a replicating React application from scratch.

There’s more detail on the benefits of this on the RxDB blog, as well as some downsides.

The Application

I wanted to build something that would benefit from the increased responsiveness.

While working, I found myself needing a quick way to write private notes and organise many small tasks. Multiple sources of notifications needed my attention, such as GitHub PRs, Slack messages, and Linear issues.

Using the issue tracker was too slow, visible to everyone, and visually distracting. I also wanted something more structured than a text file.

So the application itself is nothing revolutionary: a keyboard-driven ‘todo’ app with a minimal UI and the ability to synchronise with other services. I got fed up with notifications from multiple applications that required my attention, and I wanted them all in one place.

Summary

- Focustro is a keyboard driven ‘todo’ app with a minimal UI.

- All state is modified in-memory.

- The in-memory state is asynchronously stored in IndexedDB for persistence.

- The state can also be synchronised with a remote server.

- The remote data synchronisation has a specification written in TLA+ that can be model checked for eventual consistency.

- It uses simple React state management that is synchronised with the URL state.

- UI actions are simple functions that modify the global state of the application.

- The UI action functions can be directly called from the browser’s ‘keydown’ handler to handle key bindings.

- Postgres, Nginx, the server, the client, and a database backup service are deployed using NixOS.

Synchronising Data

The replication algorithm is described here in TLA+:

I am by no means a TLA+ expert but, in theory, this describes a simplified system and uses the TLC model checker to show that it is eventually consistent.

The application’s persistent state (projects, tasks, etc.) is stored in memory as a set of objects. Each object has a type, a unique ID and a set of properties:

{

"id": "c94fc0ad-6498-4405-82ac-8c0814fb8d80",

"_type": "task",

"title": "example task",

"createdAt": "2023-06-24T07:56:31.166Z"

}The objects are asynchronously persisted to IndexedDB, and the data can be synchronised with an external server.

When the application first loads, all objects are loaded into memory from IndexedDB.

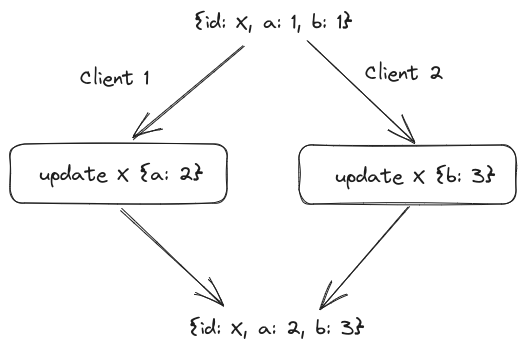

A client can atomically create objects or modify individual properties of an existing object. These properties can be updated concurrently without data loss:

Every change sent to the server returns a monotonic timestamp so that the client can request all changed objects since the last timestamp. Storage is efficient, as the server only needs to store the latest version of each object along with the timestamp it was updated at.

Data Loss

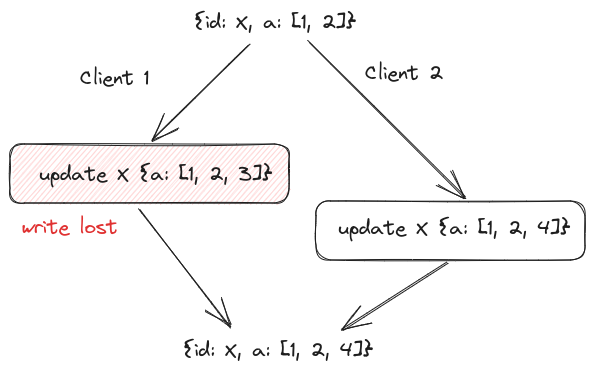

For simplicity, the current system employs “last write wins” which allows for some data loss when multiple clients write to the same property.

There are ways of addressing this problem, but I found it an acceptable trade off for simplicity.

Collections

Appending values to an array, as shown above, can lead to data loss.

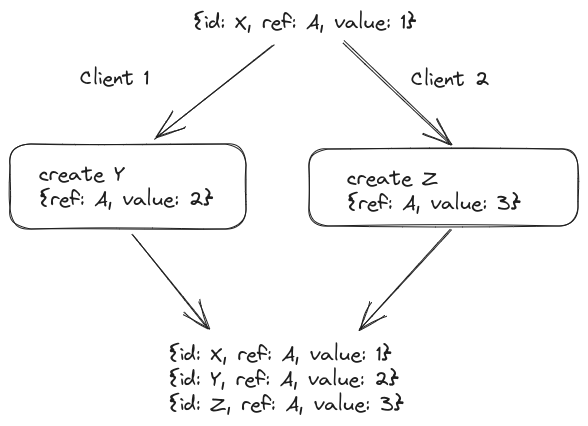

Collections of values can still be represented without data loss by using the objects like you would use foreign keys in a relational database:

React

This can be integrated with React using useSyncExternalStore.

React hooks are used to fetch objects by ID, or to fetch all objects of a given type.

In order to support the pattern described above where we need to efficiently find objects with a particular property, indexes are maintained and a hook is provided to fetch a particular value from the index.

The component is then only redrawn when objects with that particular reference are updated.

Drawbacks

In addition to the potential data loss, this system has a few weaknesses.

It loads everything into memory, which means there is a delay on first load (noticeable at around 10,000 objects) and the amount of data you can keep around is severely constrained. This can be improved by only loading indexes into memory, and lazily loading individual objects when needed.

Another concern is how to handle data migrations, especially when supporting ‘local-only’ accounts. You can no longer simply migrate using an SQL script, the migration must be run client side, and you must be sure that it is only run once. This isn’t an insurmountable problem, but it requires some careful thought.

React State Management

In addition to the synchronised persistent state, the application must also handle ephemeral state. e.g. the currently selected page, project or task. There are a large number of existing libraries to help with this (for example, Redux) but I wanted to explore a simple method.

Some state can be local to React components, but for everything else I like the way Elm handles this: by defining a set of messages that update a single global state.

This application does something simpler — it has a single global state that is updated through a mutate function, and is synchronised with React using useSyncExternalStore.

There are no reducers or messages. Each UI action is simply a function that mutates the state.

This also allows for a trivial implementation of keyboard shortcuts - simply write a ‘keydown’ handler that calls a mutating function.

This approach is not necessarily recommended for production applications (it’s very situational), but it illustrates a simple way to manage global application state with React. Understanding this interaction with React makes it easier to understand how to integrate other aspects of the application, like persistent IndexedDB state.

URLs

The URL is essentially a separate store of state. In this application it is synchronised with the global application state.

Two functions are needed, one that takes a URL and updates application state, and one that turns application state into a URL. Whenever the URL changes the first function is called and the global state is updated, and whenever the state changes and the derived URL is different to the previous URL, the new URL is pushed using the history API.

NixOS Deployment

I deploy the application to a single NixOS EC2 machine.

Nix deterministically builds software from a declarative input, and NixOS is an operating system based on this. It’s possible to declare the entire operating system, build it locally, and copy it across to a remote machine.

Here is the script I use:

#!/bin/bash

set -xe

# Build a nix server locally and copy it to a remote server

STORE_PATH=`nix-build server.nix`

nix-copy-closure --to awsnix $STORE_PATH

ssh awsnix "nix-env --profile nix-env --profile /nix/var/nix/profiles/system --set $STORE_PATH"

ssh awsnix "/nix/var/nix/profiles/system/bin/switch-to-configuration switch"The configuration.nix file defines the entire system.

PostgreSQL and Nginx are set up, along with the application server as a systemd service, and a cron to backup the database and dump it to S3.

Both the server and client have their own nix expressions for compilation.

I use npmlock2nix to compile the frontend and buildGoModule for the backend.