Applying “Make Invalid States Unrepresentable”

Here are some real life cases of applying one of my favourite principles.

I’ll try to update this as I come across good examples.

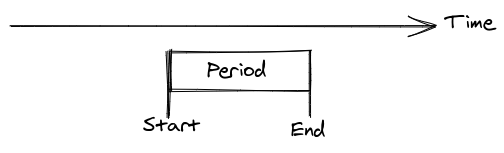

Case 1: Contiguous Time Periods

A straightforward way to represent a period of time is by its start

and end dates ((Date, Date)):

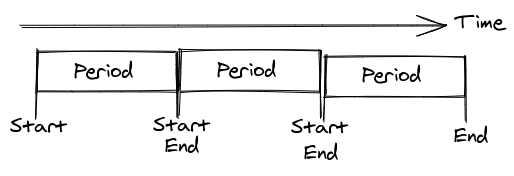

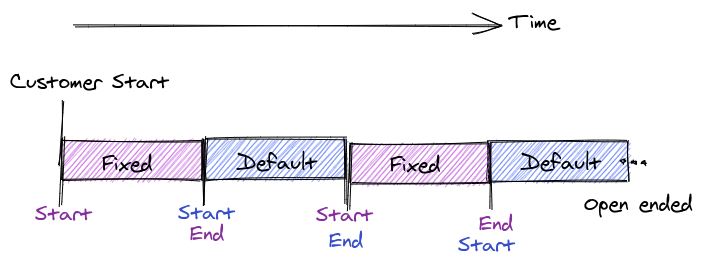

If we need to represent a timeline split in to contiguous periods, it

may be tempting to represent this as a sequence of periods (e.g. List

(Date, Date)):

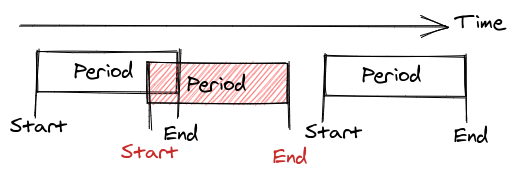

However, with this representation there can be both gaps in the timeline and overlapping periods:

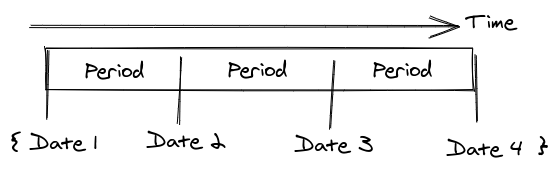

Improved Representation

We can improve this representation so that the contiguous and non-overlapping constraints always hold, and we can do this in a way that may remind you of database normalisation – by removing redundancy.

In a well formed contiguous timeline the joint start/end

of the adjacent periods are redundant. Contiguous, non-overlapping

splits can simply be represented by a set of dates (Set Date):

You can begin to see how this representation simplifies the system when you consider how to make a further split in the timeline. In the list representation, splitting a period requires carefully modifying the data-structure and ensuring constraints aren’t violated. In the ‘set of dates’ representation you simply add a date to the set.

It is sometimes still useful to represent the periods as a sequence of start and end dates. It is trivial to project the set of dates in to this form. As long as the canonical representation is the set, the constraints will still hold.

Case 2: Default Contracts

In this system a customer pays us a recurring rent based upon a contract. Contracts last for a fixed amount of time, and when they expire we fall back to a ‘default contract’. The customer can have many fixed contracts, and they can sign new contracts at any time.

This was represented as:

- A ‘customers’ table storing

- The customer start date.

- An optional end date, should the customer leave.

- A ‘contracts’ table storing

- The contract start date.

- An optional end date, for default contracts that don’t end.

- If it was a ‘fixed’ or ‘default’ contract.

This representation allows for some undesirable states that are trivial to prevent:

- The customer may have gaps in their contracts.

- A fixed contract may not have an end date.

To make matters worse, the API for these contracts allowed clients to modify each individual contract, fixed or default, without guarding against these states. This shows how a poor choice of representation propagates itself through the design of a system.

This poor choice was not just a theoretical problem - gaps in contracts were found on more than one occasion, requiring hours of engineering effort to hunt down and fix.

Improved Representation

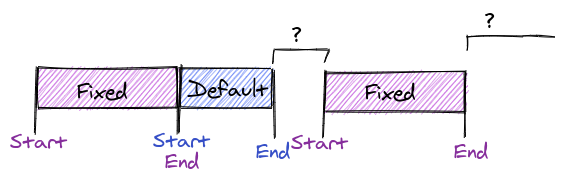

This is easily improved by removing the ‘default’ contracts from the contract table. If the customer doesn’t have a fixed contract, it is assumed they are on a default contract:

Now there can no longer be any gaps, and the end date of a contract no longer needs to be optional as it only represents fixed contracts.

It’s worth reiterating that this representation can be projected in to the previous representation using a database view if that form is more convenient. What is important is that the underlying representation enforces these constraints; it is not important how that data is viewed.

A better representation makes the manipulation of the data structure simpler. Adding a new fixed contract has been greatly simplified. There is no need to create or modify default contracts, or ensure that the contracts are contiguous.

The Influence of Object-Oriented Thinking

I think the original design happened because of atomistic, object-oriented thinking.

In this mindset, the fixed contracts are objects, the default contracts are objects, and each of these concepts must be reified as a row in a table and never inferred. Rows are seen as a serialised object instead of a true proposition.

Using an object-oriented toolbox to design a database is antithetical to quality relational design and the principle of making invalid states unrepresentable.

It may feel “simpler” on some level, as you don’t really need to think about how to map a database design to an in-memory representation; however, as we see here, this lack of forethought inevitably leads to complexity.

Further Improvements

It was left unspecified if overlapping contracts are permitted, only that gaps aren’t permitted. As it happens, this was a desirable constraint for this application and it was omitted from the first version of the article because the best solution is not clear cut.

A simple solution is to enforce this by using an ‘excludes’ constraint in the database. This is perfectly acceptable.

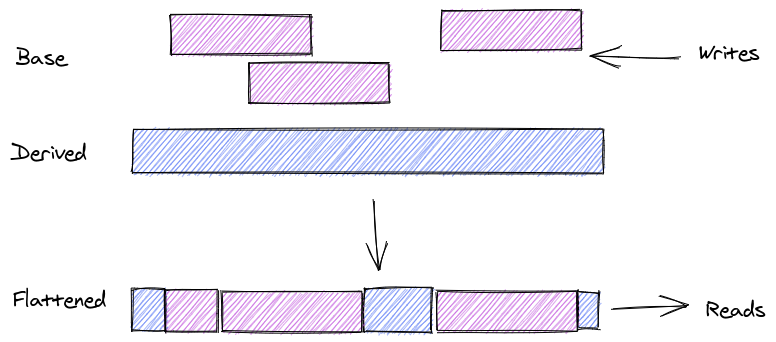

A more interesting way of doing this is to allow for overlapping contracts in the write model, but flatten them in a projection for the read model. A fixed contract is terminated by the start date of its next overlapping fixed contract.

A nice side effect of this design is that information is never lost, and you don’t need to mutate existing contracts to add new overlapping contracts.